Morning bathers in Nordhavn, Novmber 2020 (Credits: Ako Kurnosenko)

In the 443-island-country, no Dane lives further than 50 km away from the sea. And all must know it and respect it. The sea is conducive to the experience of the sublime and pleases our imagination. On the one hand, it represents a danger, on the other hand, it is an endless source of entertainment and a great escapatoire for those who play by the rules. The experience of water goes from the pleasure of bathing to the uncompromising nature of the ‘farvand’ (‘navigatable waters’ in Danish) – What can architects take from this paradoxe to build more sustainable and more resilient cities, aligned with the global development goals?

The pleasure of bathing, a Danish principle

It’s midnight in August, the sun has just set over Copenhagen, when my friend JensJakob sees bioluminescence for the first time. They are called ‘morild’, which he translates by ‘the mother’s fire’.

“I have just been swimming with morild here in the canal at Islands Brygge. The water was completely still, but I noticed something particularly beautiful about what I thought were illuminated bubbles of air which escaped my hands and forearms as I pulled through the water. I have not been swimming in the dark of night many times before, but no, this was simply magical (…) I waved my hands around, fingers outstretched, and God help me, fleeting glimpses of greenish and light blue light sprang sporadically forward only to fade just as quickly. What was there to do but swim, eyes wide open and pleased to the soul with discovery and beauty? The most stimulating 200 meters of crawl I have ever swum. (…) Some shooting stars above, thousands under the water.”

Morilds in the farvand, pretty picturesque! But that is not all. Many Danes keep bathing in winter. For their pleasure, or to awake the viking in themselves? Feelings of great freedom, adrenaline, courage, are just good enough reasons to jump into the water.

Copenhagen harbor transformation

This experience with water would not have been possible 20 years ago. In 1960, a peak of pollution in Copenhagen harbor waters led the last open bathing site to close down. It remained heavily polluted until 1989, when the municipality decided to change Sydhavn’s status from an industrial harbor to an area for offices and private housing. ‘Cargo ships, the navy and the navy dockyard were moved, and the Port’s factories and shipyards disappeared one by one’ (Danish Ministry of Environment).

In 1992, Copenhagen decided to modernize its water sewerage system in order to allow public bathing and fishing again, and to re-establish the aquatic environment of the harbor. Today, thanks to an increased capacity in overflow structures and a decrease in overflow sites, Copenhagen harbor’s waters are now as clean as outside the harbor. Fauna and flora are back, the docks have been blooming to provide recreational activities in front of homes.

This successful transformation shows that it is possible to create an attractive and varying aquatic environment in ports that have been heavily polluted and calls on other industrial harbors in the world to make the transition.

Architects play with the water’s sublime powers

Favourable for bathing, the Baltic coast provides a large playground for architects who create like poets. Imagination and architecture design spaces that are organized, conventional, but in which the nature can be approached in its greatness and wildness.

For example, White Architects built in Kastrup (South of Copenhagen) a public bathing site in the shape of a pearl, opening on the south, so it shelters bathers against the wind They tell their story: By taking the footbridge, you first avoid the sand, and when you reach the end, you turn around to contemplate the coast – before jumping straight into the water. The feeling of being in the nature and the search for sensation have their places here. Benches along the edges offer additional opportunities for leisure as well as for introspection.

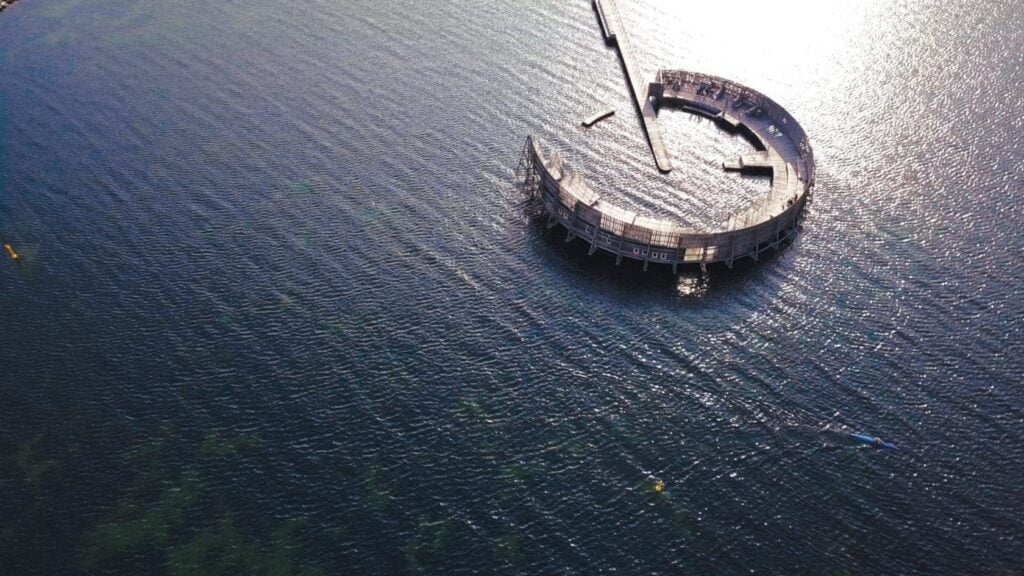

Source : Visitdenmark media – Infinite Bridge by Gjøde & Povlsgaard

One sculpture, located on Jutland’s east coast, near Aarhus, is another ambiguous invitation to the water. On the premises of an old pier for steaming boats, the Infinite Bridge (Den Uendelige Bro in Danish), built by architects Gjøde & Povlsgaard, is a circular wooden bridge on which visitors can better enjoy the landscape. Gjøde & Povlsgaard here utilize the space’s potential to enhance nature. “We have tried to create a setting where you can experience the landscape surrounding the city. Actually, it is nature, the city’s skyline, the harbor and the relationship to the water that is the true art piece,” says Johan Gjøde.” The Infinite Bridge can also be associated to the Land Art Movement, which has grown since 1960 against the commercialization of art. The movement is aimed to position art at the heart of the nature instead of in galleries, and to make use of components from the surroundings themselves.

The two artistic structures described above not only unveil the recreational dimension of water, but they also question the human being’s position both in the center of nature, but also, surrounded by it. Turning around indefinitely, would this be a sort of Danish Myth of Sisyphus ? By making people aware of their human condition, the two circular installations lead them to an impulsive revolt: they eventually choose to jump into the water, to be free.

The nature is indefinitely great while humans are indefinitely small

Is the human revolt against natural forces futile? Rybjerg Knude’s lighthouse, in the grips of the sea since its construction 100 years ago, would say Yes. The moving dune is pushing the old lighthouse towards the cliffs while the cliffs get eroded by the sea. The lighthouse is lit for the last time in August 1968 and then becomes a museum about the history and protection of the area. In 1992, the attempts to overcome the dune expansion is abandoned and Rybjerg Knude is left to its mercy. It is only in 2019 that RealDania and public actors decide to join forces to move the lighthouse 60m further inland and to refurbish the inside designed by Jaja Architects. Even if it keeps moving, the lighthouse is indeed preserved for we don’t know how many years.

Jaja Architects gave a third life to the condemned lighthouse by giving a poetic interpretation to it. Keeping the external aspect intact, they built a spiral staircase made from different types of steel inside, and added a large kaleidoscope on the top, which is put in movement by the wind and thus allows light to spread inside the tower. Acting like a mashrabiya (screen element from traditional Islamic architecture), the light stairs project light till dead corners and offers a vertiginous shadow effect to people going up the stairs. Once they have reached the top, they can contemplate the wide panorama both on the sea and the dune. All around the lighthouse, hundreds of scattered bricks, which seem to have been blown by a storm, give the area a heavy but liberating atmosphere and a certain humility to the nature’s conquestador. Time there may have stopped.

While we wait for the sea, art and architecture bring up awareness

To meet the 11th Sustainable Development Goal (set by the United Nations), tomorrow’s architecture should “make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”. Yet, the occurrence of rain in Copenhagen is expected to increase by 30% and the level of the see is expected to rise from 33 to 61cm by 2100 (European Commission). The Danish city of Vejle (114,000 inhabitants), whose fjord is part of the flood-risk area, called architects to make proposals for a storm surge protection of the fjord.

‘While we wait for the sea’ (architects J. Houser et J. Johansen) is the name given to the second winning proposal in the competition, after the project ‘Membrane’ (J. Philipsen, A. H. Williamson, L. Brando). Both master plans are developed in a design doing with water, instead of against water. The membrane is acting like a porose structure, a permeable shell which could keep protecting the fjord while being partially under water.

Artists as well are extensively exploring what could be called here “the membrane paradigm”. In his latest exhibition, Event Horizon, taking place in Copenhagen’s old cisterns, Tomas Saraceno opens up new perspectives on housing adaptation to climate change. The cisterns were the largest reservoir of drinkable water in Copenhagen between 1856 and 1933. Visitors navigate a boat through the darkness, under the cistern’s arcades and between its massive columns. During the slow journey, lights, shadows and reflections play together and let appear light spheres and metallic spider nets that Saraceno hung in the air. Despite a strong contrast in shapes and weights between the cistern and the sculptures, the ensemble’s harmony carries visitors into their visionary imagination. Who knows, maybe one day we will build oxygen bubbles to survive under water, like the formidable spider Argyroneta aquatica?

Experiences of water remind us that nature always takes over, and also that we can emancipate and feel more free by respecting it. The experience of the sublime in arts and architecture reinforces our awareness of climate change and contributes to further imagining a world where human beings inhabit the nature and the nature inhabits human beings. The depollution of Copenhagen’s harbor depollution, Land Art on the Baltic shore, the Danish education system are great examples of the fluidity and porosity between disciplines here in Denmark. It is likely to result in the integration of multiple perspectives in the construction of tomorrow’s cities.

It is likely to result in the integration of multiple perspectives in the construction of tomorrow’s cities. Anupama Kundoo, a famous Indian architect currently exhibiting in Louisiana museum for contemporary arts (Denmark), has set up three principles that are replicable from India to Denmark and could make future architecture more resilient to the next floods and droughts: Make use of natural and local materials, align with the language of the surrounding environment, build for a minimized energy consumption. Now, it is your turn to jump into the water.

Annabelle Moine (LinkedIn)